Origins — The Episcopal Church Divided

At the beginning of the 1960s, there seemed to be no end in sight for the post-war boom in membership for the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America. Communicant numbers rose rapidly, while the number of baptized topped three million in the late 1950s. It was a diverse, vibrant, and largely orthodox church which appealed to a wide cross section of American society, though it was always a mainly middle class church, closely paralleling the Presbyterians in its demographic. However, the retirement of Arthur C. Lichtenberger (1900-1968) as presiding bishop in 1964 seemed to herald a major change in direction for the church, as the liberalizing forces, contained by the relatively conservative social conventions of the 1950s, asserted themselves in the mid to late 1960s.

The post-war centralization of the church’s administration had significantly changed the way in which the national church and the dioceses related to one another. National policies and national programs asserted themselves as of the old decentralized model of the Episcopal Church. Bishop Sherrill, presiding bishop 1946-1958, was an enthusiastic organizer and was able to create a new central administration based on “815” the new, larger Episcopal Church headquarters in New York City, and Seabury House in western Connecticut, which acted as a national conference center and retreat house as well as serving as the presiding bishop’s official residence. Sherrill was comparatively liberal but of the old school, which remained essentially ‘evangelical’ in style. His successor Bishop Lichtenberger (1900-1968) of Missouri represented the more socially aware element in the church, and during his tenure, the liberalizing forces at work in the seminaries in the 1950 began to become more influential. Lichtenberger was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in late 1963 and retired as presiding bishop following the 1964 General Convention. The new presiding bishop was the relatively youthful and liberal Bishop Hines of Texas, who seemed to want to promote a more socially-aware and broadly-based Episcopal Church. He singularly failed to deal with the theological eccentricities and heresies of Bishop James Pike of California (1913-1969), who abandoned the doctrine of the Holy Trinity and increasingly showed an interest in Eastern religions and spiritualism. Despite demands for Bishop Pike to be disciplined, the House of Bishops waffled until Pike received a mild censure in 1966, and shortly afterwards resigned.

The desire of the General Convention to apologize to everyone and anyone for the church’s not-so-politically-correct past took interesting forms. Money was diverted from traditional mission work to support social projects in the slums, and inevitably some of this money was assigned to an organization aligned with the Black Panthers, which provoked a major row in the General Convention of 1970. Trial liturgies were introduced in 1967 and again in 1970, reflecting similar moves in the Roman Catholic Church, and a considerable caucus began to push for women’s rights including liberalizing the church’s teaching on marriage (1967), abortion (1973), and holy orders (1976). The liberal drift of the Episcopal Church culminated in the 1973 decision to ordain women to the diaconate in place of the traditional office of deaconess. One suspects that most delegates to the 1973 General Convention were not sufficiently theologically-aware to realize that this decision made a split in the church inevitable. Ordaining women as deacons put them into major orders for the first time in church history — if one excludes some funny goings-on in heretical sects in the days before Nicaea — and this was potentially explosive! Unsurprisingly, calls for the traditional and catholic wings of the Episcopal Church to organize and resist innovation became even louder — and became ever more strident with the illegal ordination of the “Philadelphia 12” in 1974, the General Convention’s decision to allow women priests in 1976, and the authorization of a new Book of Common Prayer in 1976. This opened a deep division between conservatives, moderates, and liberals, and one somewhat suspects that the decision to elect the relatively-conservative Bishop Allin as the new presiding bishop reflected growing worries about the church’s future. Unfortunately, by the time Allin was elected, it was too late to make any real difference.

The Die is Cast

The social and moral crisis of the 1960s had already produced a series of breakaways from the Episcopal Church. The first was the Anglican Orthodox Church (1963), which largely reflected the old Southern low church tradition but had a highly-centralized structure and a controlling leadership. This was followed by the Southern Episcopal Church (1965), American Episcopal Church (1968) — both of which were more ‘broad church’ in outlook — the United Episcopal Church of America (1970), and the Anglican Episcopal Church of North America (1972). A complicated series of transferences and mergers followed so that, by 1976, there were two main groups of Continuers: the American Episcopal Church mainly in the South, and the Anglican Episcopal Church of North America mainly in the western states. Unfortunately, none of the movers and shakers on the conservative side of the Episcopal Church was prepared to take these pre-existing bodies seriously, alleging invalid or at least questionable orders, and in some cases, casting aspersions about the political leanings of the clergy.

The St. Louis Congress

As a result, the Fellowship of Concerned Churchmen organized a congress to meet in St. Louis, Missouri September 24-26, 1977, essentially to discuss the crisis in the Episcopal Church, but in reality, to organize a new orthodox Anglican body in the United States and Canada. The Episcopal patron of the congress was the Rt. Rev. Albert A. Chambers, the retired Episcopal bishop of Springfield, Illinois, who had already given episcopal oversight to a number of parishes that left the Episcopal Church. The Congress voted to create a new church, initially called the Anglican Church of North America (Episcopal) — not to be confused with the 2009 chartered body of the same name — and called for the erection of dioceses to receive parishes from the Episcopal Church and found new missions. The Congress also produced the “Affirmation of St. Louis,” a four-page document outlining a road map and general principles for the creation of a new Anglican church in the United States. The original dioceses of the ACNA(E) were the Diocese of the Holy Trinity, the Diocese of the Midwest, the Diocese of the South, and the Diocese of Christ the King. Developments in Canada lagged a little behind the U.S., with Eastern Canada being served initially by the Diocese of the Midwest and Western Canada by the Diocese of the Holy Trinity.

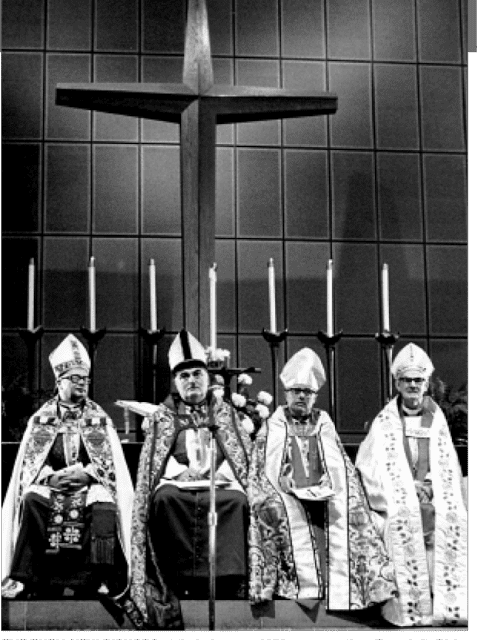

The four priests selected to serve as bishops in the new church were the Rev. C. Dale D. Doren (Midwest), James O. Mote (Holy Trinity), Robert S. Morse (Christ the King), and Peter Watterson (South). Order was taken for their consecration in January 1978 in Denver, Colorado. The authorities in the Episcopal Church, with the assistance of Donald Coggan, the Archbishop of Canterbury, applied pressure to any bishop thought to be sympathetic, in the hopes of discouraging their attendance. In the end, Albert Chambers, Francisco Pagtakhan, Mark Pae, Cyril Eastaugh, and Charles Boynton indicated their intent to be present. However, Mark Pae was ordered not to attend by the Archbishop of Canterbury; Bishop Eastaugh was unable to travel following surgery; and Bishop Boynton was hospitalized with chest pains a few days before the consecration. As a result, it was decided that Doren, who had received letters of consent from Pae and Boynton, would be consecrated first, and then he would serve as second co-consecrator for Mote, Morse, and Watterson. The Living Church, the Episcopal Church’s house journal, made much of the alleged irregularities in the Denver consecrations, but had they been better church historians they would have realized that the situation, though unusual, was analogous to the beginnings of the Old Catholic church of the Netherlands and the early days of the Catholic hierarchy in the United States!

The next few years were chaotic. A Constitution Assembly embarked on a major revision of the constitution and canons, which not only proved to be time consuming but controversial. The initial decision to retain in the interim the 1964 edition of the Constitution and Canons of the Protestant Episcopal Church seems to have been swept aside by the white heat of innovation. To complicate matters future, the new church was growing like topsy, and new dioceses were founded to serve the Mid-Atlantic States, the Southwest, the Northeast (Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York), and the Missouri Valley over the next few years. As most of these new dioceses elected Anglo-Catholic bishops, an imbalance was to develop within the new church, which was accidentally reflected in a name change from the Anglican Church in North America to the Anglican Catholic Church (ACC).

Part of the problem was that the “Affirmation of St. Louis” was not quite as Anglican as its framers liked to protest. There was a small but significant shift away from the doctrines of the Thirty-nine Articles and the Book of Homilies towards a more mediaeval catholic stance. The “Affirmation” contained some small amendments that had big consequences, including a declaration that the Holy Eucharist is a sacrifice, an idea strongly repudiated by the Articles of Religion; strongly asserting the doctrine of apostolic succession; accepting that the church has seven sacraments, a hitherto disputed notion — albeit in a way that allowed a distinction to be made between the dominical sacraments and the others; and making the Bible as interpreted by the seven ecumenical councils of the ‘undivided’ church the doctrinal standard, as opposed to the six councils traditionally accepted by the Book of Homilies of the Church of England, or the first four councils as was considered normative by no less a luminary than Bishop Lancelot Andrewes (1555-1626). While acceptable in the United States and Canada, these notions made the “Affirmation of St. Louis” largely non-exportable to those areas of the Anglican Communion where low churchmen and evangelicals predominated. Even within the U.S., where broad churchmen largely accepted these propositions, those not of the Anglo-Catholic persuasion tended to downplay these provisions, and continued to operate their parishes on middle-of-the-road traditional lines. On the other hand, the Anglo-Catholics used them as vindication of their version of American Anglicanism, turning it into the American Catholic Church that the Episcopal Churchhad never been.

The inevitable train wreck occurred when the first draft of the ACC’s Constitution and Canons came up for approval in 1981. Two mainly Anglo-Catholic dioceses — Christ the King, Southeastern States — did not send delegates to the provincial synod, but there was still sufficient representation to allow the new Constitution to be adopted. Bishop Doren, the senior bishop in the ACC, retired at this time, citing health grounds, but it was actually because of his continual conflicts with the Anglo-Catholic majority in the college of bishops. The 1981 Provincial Synod also marked the end of the involvement of Bishops Morse and Watterson, numbers three and four in the ACC succession, who ceased to be involved in the synodical structures of the church at this time. Only Bishop Mote and the bishops consecrated after the initial Denver consecrations remained actively involved in the ACC.

The United Episcopal Church is Founded

Bishop Doren did not remain retired for long. By October 1981, he had been approached by a group of broad and low church clergy and laymen with the idea of creating a church that would simply be a continuation of the old Protestant Episcopal Church, but with a tighter doctrinal basis, welcoming of traditional low churchmen. Doren embraced the idea, and the organizing convention of the United Episcopal Church of North America (UECNA) was held in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania in October 1981. The draft constitution of the new UECNA was clearly derived from the 1958 Constitution and Canons of the Protestant Episcopal Church, with remarkably few changes. The biggest single change was specifically mentioning the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (1563/1801) in the Declaration of Conformity contained in the Constitution of the Church. The title ‘Presiding Bishop’ was changed to ‘Archbishop’ with the additional requirement that the bishop elected be over the age of 55. Some small changes were made to the provisions for the General Convention, but otherwise it was a remarkably conservative document. Bishop Doren was, at that time, based in Northwest Pennsylvania, and the original diocese, that of the Ohio Valley, focused on planting parishes in southern Ohio and northern Pennsylvania. Additional work soon started in the South — Florida and Alabama, especially — demonstrating that the UECNA was fulfilling a need within the relative young Continuing Church movement.

By the time of the second General Convention in 1984, the UECNA had grown to the point that it needed to be divided into missionary districts, and additional bishops were required to carry forward the work of the church. The 1984 General Convention chose to divide the church into four missionary districts, in addition to the Diocese of the Ohio Valley, of which Archbishop Doren was the ordinary. These were Midwest, East, South, and West. Albion Knight was appointed to the Missionary District of the East, and John Gramley to the South the following year. This set the pattern for the next ten years.

Archbishop Knight

Archbishop Doren reached retirement age in 1987 and was succeeded as archbishop by the Rt. Rev. Albion W. Knight, Jr., whose grandfather had served as the first Episcopal bishop of Cuba at the beginning of the twentieth century, then as bishop coadjutor of New Jersey. Archbishop Knight had been career Army, retiring as a brigadier general. He had been ordained in the Episcopal Church in the mid-1960s after studying at Virginia Seminary, and had been active in parish ministry throughout this period. Knight’s outlook might fairly be described as low church evangelical, but he was nonetheless able to negotiate an inter-communion agreement with the ACC, on the basis of both jurisdictions maintaining their distinctive traditions. This reflected his unease at the fragmented nature of the Continuum and an ongoing desire for greater unity.

His period as archbishop was one of considerable expansion of the UECNA. At the time of Archbishop Doren’s retirement in 1987, the UECNA had about 20 parishes overseen by three bishops: Doren, Knight, and Gramley. This increased to almost forty over the next five years, and saw the expansion of the UECNA to the West Coast, with the denominational seminary — originally called Latimer Seminary and later Doren Seminary — based out of La Brea, California. However, an internal dispute in 1989-90 led to the departure of a handful of parishes and the seminary.

Bishop Knight retired as presiding bishop at the 1992 General Convention to pursue the vice-presidency of the United States as the candidate for the U.S. Taxpayers’ Party. Needless to say, this was a somewhat futile undertaking, but at 68, Bishop Knight probably felt that the UECNA could do with younger leadership.

Decline and Revival

Bishop Gramley succeeded as presiding bishop in 1992 (the 1992 draft canons dropped the use of the term ‘Archbishop’) at a time when the UECNA was looking to the future with great optimism. He had been a missionary in Africa for 17 years before returning to the USA in 1980 and aligning shortly afterwards with the UECNA. He had been appointed missionary bishop of the South in 1985, and was in good health at the time of his election as Presiding Bishop. Unfortunately, shortly after his installation as presiding bishop, Bishop Gramley began to suffer significant medical problems, which greatly hampered him in his work as both missionary bishop of the South and presiding bishop. Sadly, 1992–1996 saw a significant decrease in the size of the UECNA, mainly due to the illness of the presiding bishop and tensions between the other UECNA bishops. When the General Convention met next in 1996, the decision was made to elect a successor to Bishop Gramley and to secure his consecration by bishops of the ACC. The Rev. Stephen C. Reber was elected as bishop coadjutor, but the ACC backed out of the consecration at the last moment, due to difficulties within their own college of bishops. Nevertheless, Reber was consecrated as by the Rt. Rev. Robert C. Harvey, assisted by Bishops Miller and Gramley, in September 1996.

Bishop Gramley’s retirement and death left Bishop Reber as the sole bishop and presiding bishop of the UECNA. At that time, only about 10 parishes remained affiliated with the jurisdiction, most having closed or drifted away in the long years of Bishop Gramley’s increasing incapacity. During his first years as presiding bishop, Reber drove 30,000 miles, reestablishing contact with parishes that were formally (or in some cases, formerly) affiliated to the UECNA. By the end of the 1990s, the UECNA had grown to 18 congregations and had entered into a short-lived inter-communion agreement with the Anglican Province of America (APA). This caused the ACC to suspend their existing agreement with the UECNA, as the APA was not part of the St. Louis Continuum. The agreement between the UECNA and APA was in turn suspended when the APA joined in a partnership agreement with the Reformed Episcopal Church (REC).

By 2002, the UECNA had grown sufficiently for Bishop Reber to call for the election of a suffragan bishop. This occurred during a period of slow but sustained growth, which ended with some twenty-seven congregations affiliated with the UECNA in 2007-8. The Rt. Rev. Leo Michael was active as a suffragan bishop in the UECNA from 2005-7 before being elected as bishop of the Great Plains in the Holy Catholic Church–Anglican Rite. Unfortunately, Bishop Michael did not go to his new jurisdiction empty handed, but caused a minor schism, which slightly reduced the overall number of UECNA congregations.

More Talks with the ACC

There had long been interest in restoring the inter-communion agreement with the ACC which had been ended in 1999. Bishop Michael, then newly-consecrated, contacted Archbishop Haverland with a view to restoring the relationship in 2005, and a new inter-communion agreement was signed on Ascension Day 2006. This coincided with increased interest within both the UECNA and the ACC on reconciling the two churches within a common structure. In cooperation with Archbishop Reber, Bishop Hutchens of the ACC drew up a pathway document, proposing a method by which unity could be achieved, and this was brought to both the 2007 ACC General Synod and the 2008 UECNA General Convention for approval. However, a general lack of follow-through from both churches resulted in this document ultimately being a dead letter, especially when it became clear that what was contemplated by the ACC was not so much a merger of the UECNA as the dissolution of the UECNA and the absorbing of its parishes into the larger body.

During the period when the UECNA was looking towards merger with the ACC, it was decided to elect three suffragan bishop to serve both the UECNA and, by invitation, both the ACC and Anglican Province of Christ the King (APCK). At the 2008 General Convention, the Revs. Peter D. Robinson, Wesley Nolden, and Samuel Seamans were elected as bishops. They were consecrated by Archbishop Reber, assisted by Bishops Hutchens of the ACC and Wiygul of the APCK the King in St. Louis, Missouri on January 10, 2009. Bishop Nolden rapidly abandoned the UECNA for the REC and then the Anglican Church in North America, and Bishop Seamans transferred to the REC at the end of 2009. This period of instability reduced the size of the UECNA by about a third, but ended with the election and consecration of the Very Rev. Glen Hartley as bishop of the Missionary District of the South in April 2010. This was accompanied by the announcement that the National Council had designated the Right Rev. Peter D. Robinson to act as presiding bishop of the UECNA following Bishop Reber’s retirement in September.

The Present Situation

Bishop Robinson succeeded Archbishop Reber on September 6, 2010 and immediately set about two tasks. The first was calling the 2011 General Convention, which met in Heber Springs, Arkansas, and of determining whether the UECNA’s future lay as a non-geographical diocese of the ACC or as an independent jurisdiction.

The 10th General Convention met in May 2011 and was well-attended. There was a great sense that this was a convention at which some major decisions about the future would be made and that the course of the UECNA over the next decade would be set. Bishop Robinson was formally elected as the presiding bishop of the jurisdiction upon the nomination of the House of Bishops. This was ratified unanimously by the House of Deputies. Discussions on mission work, church planting, and the budget then followed, with the assumption being made that the UECNA would continue as an independent jurisdiction. The final session of the General Convention saw a motion for a second ratifying vote on the 2008 pathway document moved on the floor of the House of Deputies, but this failed for the lack of a second.

Initially little changed after the 2011 General Convention. The events of 2009-10 had reduced the UECNA to just sixteen churches, so there was a real need to consolidate its position. However, events dictated that the Eastern Missionary Diocese received a group of clergy and parishes from the Orthodox Anglican Church, following the partial collapse of that jurisdiction in early 2012. Additional parishes were received from the same source in the West, and the UECNA grew from 15 to 21 congregations during the late summer of 2012. Additional churches in Kentucky affiliated to the UECNA in 2013. In January 2014, Bishop Robinson made an appeal to the leaders of other traditional episcopal bodies to work for consolidation of the traditional Anglican work on the basis of the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion and traditional Book of Common Prayer within a single jurisdiction. This led to visits from Bishop George Conner, presiding bishop of the Anglican Episcopal Church, U.S. (AECUS), just ahead of the 2014 General Convention; and from Bishop David Hustwick, bishop of the Diocese of the Great Lakes, to Convention. This began the process that brought both of these smaller jurisdictions into the UECNA. The Diocese of the Great Lakes affiliated in July 2014, and the AECUS in February 2015.

Since the 2014 General Convention, the UECNA has continued to experience modest growth with parishes and missions being added in New York, North Carolina, and Virginia, with the total number of congregations now approaching 30. The 2017 and 2020 General Conventions adopted constitutional and canonical changes intended to serve as the springboard for further growth and mission activity.